Florence Nightingale Hospital

for Gentlewomen

for Gentlewomen

19 Lisson Grove, NW1 6SH

Medical

dates:

Medical

character:

General

The Establishment for

Gentlewomen during Temporary Illness opened on 15th March 1850 at No. 8

Chandos Street, Cavendish Square. It had been founded in1849 by Lady Charlotte Canning

(1817-1861) and a group of philanthropic ladies as a nursing home to

provide treatment for 'educated women' of moderate means who were

temporarily ill, but too poor to afford private medical care and too

refined to be admitted to a public hospital; most patients were able to

contribute something towards their stay.

The Establishment had 6 beds. As well as a Matron, a cook, kitchen maid, housemaid and manservant were employed. Nurses were engaged as necessary. Surgeons and physicians contributed their services gratuitously.

However, the institution did not prosper, mainly due to inability to find a competent Matron and efficient nurses. In early 1853 the Ladies Committee changed its policy and asked Florence Nightingale if she would consider becoming its Lady Superintendent, dealing with nursing and administrative matters. She agreed, on condition that she would be allowed to reorganise the nursing home and also use it as a training school for nurses. She was appointed in late April - her first senior nursing job.

She began her duties on 12th August 1853, a week before the home moved to No. 1 Upper Harley Street (in 1866 Upper and Lower Harley Street were unified into Harley Street; No. 1 Upper Harley Street became No. 90 Harley Street).

The 3-storey building had an attic and a basement. Ms Nightingale soon used her administrative skills to good effect. A hot water supply was installed to all floors, as well as a windlass to bring up hot food from the basement kitchen. She changed the grocer and the coal merchant and had the kitchen range replaced. She also changed the name of the home to the Hospital for Gentlewomen during Illness, and made it non-denominational. While the patients were mainly governesses, she also permitted the wives and daughters of the clergy and those of naval, military and other professional men to be admitted.

The Hospital had 20 beds. The weekly charge for an in-patient was 1 guinea (£1.05) for a single room, or 14 shillings (£0.70) for a bed in a 3- or 4-bedded ward (the beds were sectioned off by curtains and were known as cubicles). A letter from a subscriber was not necessary, but two letters of introduction (with particulars of social position and income) from persons to whom the applicant was known were necessary, as was a guarantee as to weekly charges and expenses. Applicants were required to produce a certificate from a medical practitioner as to fitness for admission (cases of infectious diseases or mental illness were ineligible).

Having instituted these reforms, Ms Nightingale departed for the Crimea in October 1854. Her training school for nurses never materialised as it was deemed impractical.

In 1873 the Hospital's income was £4,510 from all sources. Payments from the patients amounted to £839 16s 0d (£839.80), while expenditure was £3,110 13s 3d (£3,110.66).

By 1875 the weekly charge (including board, lodging, medical attendance and medicine) for a bed in a single room had increased to 23 shillings £1.15), while a bed in a double room cost 19 shillings (95p) and a cubicle in a ward 15 shillings (75p). Children were admitted on special terms for the same fees.

By 1900 the Hospital was in financial difficulties. Its running costs were £2,424 9s 1d (£2,424.45) for that year, but income only £1,770 19s 6d (£1,770.97) - a shortfall of £653 9s 7d (£953.48). The weekly average cost of an in-patient was £3 10s 7d (£3.53). Patients contributed towards the cost of their maintenance, meeting half the expenses of the institution. In 1900 some 164 patients had been treated, of whom 145 had been cured; 123 operations had been performed.

The lease on No. 90 was due to expire in 1909 and the Committee decided to build a nursing home nearby. A plot of land was purchased in Lisson Grove and an Appeal launched for the project, greatly aided by the involvement of Florence Nightingale herself.

The foundation stone for the new building was laid on 18th January 1909 by the Duchess of Albany. The Hospital's lease expired before building works had been completed and it was forced to closed for a few months.

The purpose-built hospital was officially opened on 7th March 1910 by the Princess of Wales (who later became Queen Mary). It had 32 beds.

The wards were arranged on two floors - each had a general ward with 10 beds, each curtained off to make a cubicle, and a small ward with 2 beds. Each floor also had 4 single rooms (one of which served as a chapel until one could be prepared on the first floor). The single rooms were simply and comfortably furnished, with a low easy chair for patients well enough to sit up out of bed. The ward balconies were large enough for patients to be wheeled out in their beds.

The weekly charge for a single room was £2 10s (£2.50), and £1 5s (£1.25) for a cubicle in a ward.

The operating theatre and its annexes were on the top floor. They were well equipped with modern lighting and facilities. The spacious flat roof could be accessed from this floor.

The Nurses' Sitting Room and Dining Room, adjacent to each other, contained some pieces of furniture from No. 90 Harley Street.

Following Florence Nightingale's death on 13th August 1910, the Hospital was renamed the Florence Nightingale Hospital for Gentlewomen.

In 1912 work began on an extension which would provide 6 extra beds. This was opened on 14th November 1913 by the Duchess of Albany.

At the outbreak of WW2 in 1939 the Hospital joined the Emergency Medical Service with 38 beds. A fixed First Aid Post was established at the Hospital but later the building became an Emergency Rest Centre for people whose homes had been destroyed by bombs. The LCC took over the basement for use as a British Restaurant.

In 1948 the Hospital was disclaimed (exempted) from the NHS and remained independent.

By the late 1950s the weekly charge for a single room was from 8 to 11 guineas (£8.40 to £11.55), and 4 guineas (£4.20) for a cubicle. The patients were 'educated women of limited means and those of the professional classes'.

In 1978 the Hospital was sold to BUPA due to rising costs and inflation. It became the Nightingale BUPA Hospital.

In its 125-year lifespan, it had acquired a confusing array of names. Most are listed below:

Establishment for Gentlewomen during Illness

Establishment of Invalid Gentlewomen

Florence Nightingale Hospital for Gentlewomen

Florence Nightingale Hospital for Ladies of Limited Means

Harley Street Home for Sick Governesses

Hospital for Invalid Gentlewomen

Hospital for Sick Governesses

Hospital for Sick Ladies

Institute for Gentlewomen during Illness

Institute for Sick Governesses in Distressed Circumstances

Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen

Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen

in Distressed Circumstances

Invalid Gentlewomen's Institution

Sanatorium for Sick Governesses

The Establishment had 6 beds. As well as a Matron, a cook, kitchen maid, housemaid and manservant were employed. Nurses were engaged as necessary. Surgeons and physicians contributed their services gratuitously.

However, the institution did not prosper, mainly due to inability to find a competent Matron and efficient nurses. In early 1853 the Ladies Committee changed its policy and asked Florence Nightingale if she would consider becoming its Lady Superintendent, dealing with nursing and administrative matters. She agreed, on condition that she would be allowed to reorganise the nursing home and also use it as a training school for nurses. She was appointed in late April - her first senior nursing job.

She began her duties on 12th August 1853, a week before the home moved to No. 1 Upper Harley Street (in 1866 Upper and Lower Harley Street were unified into Harley Street; No. 1 Upper Harley Street became No. 90 Harley Street).

The 3-storey building had an attic and a basement. Ms Nightingale soon used her administrative skills to good effect. A hot water supply was installed to all floors, as well as a windlass to bring up hot food from the basement kitchen. She changed the grocer and the coal merchant and had the kitchen range replaced. She also changed the name of the home to the Hospital for Gentlewomen during Illness, and made it non-denominational. While the patients were mainly governesses, she also permitted the wives and daughters of the clergy and those of naval, military and other professional men to be admitted.

The Hospital had 20 beds. The weekly charge for an in-patient was 1 guinea (£1.05) for a single room, or 14 shillings (£0.70) for a bed in a 3- or 4-bedded ward (the beds were sectioned off by curtains and were known as cubicles). A letter from a subscriber was not necessary, but two letters of introduction (with particulars of social position and income) from persons to whom the applicant was known were necessary, as was a guarantee as to weekly charges and expenses. Applicants were required to produce a certificate from a medical practitioner as to fitness for admission (cases of infectious diseases or mental illness were ineligible).

Having instituted these reforms, Ms Nightingale departed for the Crimea in October 1854. Her training school for nurses never materialised as it was deemed impractical.

In 1873 the Hospital's income was £4,510 from all sources. Payments from the patients amounted to £839 16s 0d (£839.80), while expenditure was £3,110 13s 3d (£3,110.66).

By 1875 the weekly charge (including board, lodging, medical attendance and medicine) for a bed in a single room had increased to 23 shillings £1.15), while a bed in a double room cost 19 shillings (95p) and a cubicle in a ward 15 shillings (75p). Children were admitted on special terms for the same fees.

By 1900 the Hospital was in financial difficulties. Its running costs were £2,424 9s 1d (£2,424.45) for that year, but income only £1,770 19s 6d (£1,770.97) - a shortfall of £653 9s 7d (£953.48). The weekly average cost of an in-patient was £3 10s 7d (£3.53). Patients contributed towards the cost of their maintenance, meeting half the expenses of the institution. In 1900 some 164 patients had been treated, of whom 145 had been cured; 123 operations had been performed.

The lease on No. 90 was due to expire in 1909 and the Committee decided to build a nursing home nearby. A plot of land was purchased in Lisson Grove and an Appeal launched for the project, greatly aided by the involvement of Florence Nightingale herself.

The foundation stone for the new building was laid on 18th January 1909 by the Duchess of Albany. The Hospital's lease expired before building works had been completed and it was forced to closed for a few months.

The purpose-built hospital was officially opened on 7th March 1910 by the Princess of Wales (who later became Queen Mary). It had 32 beds.

The wards were arranged on two floors - each had a general ward with 10 beds, each curtained off to make a cubicle, and a small ward with 2 beds. Each floor also had 4 single rooms (one of which served as a chapel until one could be prepared on the first floor). The single rooms were simply and comfortably furnished, with a low easy chair for patients well enough to sit up out of bed. The ward balconies were large enough for patients to be wheeled out in their beds.

The weekly charge for a single room was £2 10s (£2.50), and £1 5s (£1.25) for a cubicle in a ward.

The operating theatre and its annexes were on the top floor. They were well equipped with modern lighting and facilities. The spacious flat roof could be accessed from this floor.

The Nurses' Sitting Room and Dining Room, adjacent to each other, contained some pieces of furniture from No. 90 Harley Street.

Following Florence Nightingale's death on 13th August 1910, the Hospital was renamed the Florence Nightingale Hospital for Gentlewomen.

In 1912 work began on an extension which would provide 6 extra beds. This was opened on 14th November 1913 by the Duchess of Albany.

At the outbreak of WW2 in 1939 the Hospital joined the Emergency Medical Service with 38 beds. A fixed First Aid Post was established at the Hospital but later the building became an Emergency Rest Centre for people whose homes had been destroyed by bombs. The LCC took over the basement for use as a British Restaurant.

In 1948 the Hospital was disclaimed (exempted) from the NHS and remained independent.

By the late 1950s the weekly charge for a single room was from 8 to 11 guineas (£8.40 to £11.55), and 4 guineas (£4.20) for a cubicle. The patients were 'educated women of limited means and those of the professional classes'.

In 1978 the Hospital was sold to BUPA due to rising costs and inflation. It became the Nightingale BUPA Hospital.

In its 125-year lifespan, it had acquired a confusing array of names. Most are listed below:

Establishment for Gentlewomen during Illness

Establishment of Invalid Gentlewomen

Florence Nightingale Hospital for Gentlewomen

Florence Nightingale Hospital for Ladies of Limited Means

Harley Street Home for Sick Governesses

Hospital for Invalid Gentlewomen

Hospital for Sick Governesses

Hospital for Sick Ladies

Institute for Gentlewomen during Illness

Institute for Sick Governesses in Distressed Circumstances

Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen

Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen

in Distressed Circumstances

Invalid Gentlewomen's Institution

Sanatorium for Sick Governesses

Present

status (February 2010)

The building became the Capio

Nightingale Hospital, specialising in the treatment of psychological

and emotional problems, addictions and eating disorders.

Update: December 2015

It is currently the Nightingale Hospital, run by Florence Nightingale Hospitals Ltd, which was the UK subsidiary of the Sweden-based European healthcare provider Capio Groupe.

In 2014 Florence Nightingale Hospitals Ltd was acquired by Groupe Sinoue for an undisclosed sum.

No. 90 Harley Street.

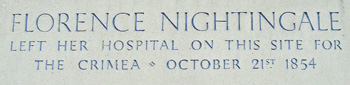

A plaque on the front elevation of the building.

N.B. Photographs above obtained in August 2011.

N.B. Photographs below obtained in

February 2010.

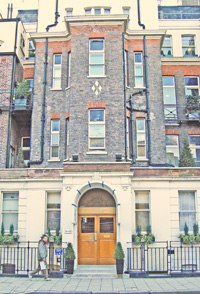

The Nightingale Hospital in Lisson Grove, built in 1909, stuccoed to the ground and top floors (above and below).

The main entrance.

The central section bears the name 'Florence Nightingale'.

(Author unstated) 1875 Provident institutions and Out-Patient Departments. British Medical Journal 2 (758), 49.

(Author unstated) 1912 The Florence Nightingale Hospital for Gentlewomen. British Journal of Nursing, 1st June, 438.

(Author unstated) 1913 The Florence Nightingale Hospital. British Journal of Nursing, 22nd November, 431-432.

Granger P 2009 Up West: Voices from the Streets of Post-War London. London, Corgi.

Helmstadter C, Godden J 2011 Nursing Before Nightingale, 1815-1899. Farnham, Ashgate.

Hibbert C, Weinreb B, Keay J, Keay J 2010 The London Encyclopaedia, 3rd Edn. London, Macmillan.

Matheson A 1913 Florence Nightingale. A Biography. London, Thomas Nelson & Sons.

McDonald L (ed) 2009 The Nightingale School: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, Vol.12. Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

McDonald L (ed) 2012 Florence Nightingale and Hospital Reform: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, Vol.16. Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Nash P 1925 A Short Life of Florence Nightingale. New York, Macmillan Co.

Smith M, Sakula A 1994 Hospital Names. London, RSM Press.

http://archive.spectator.co.uk

http://digital.nls.uk

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk

http://johnsnow.matrix.msu.edu

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz

http://pastscape.org.uk

http://scienceflix.digital.scholastic.com

http://wiki.answers.com

https://news.google.com

www.londonancestor.com

www.londonremembers.com (1)

www.londonremembers.com (2)

www.aim25.ac.uk (1)

www.aim25.ac.uk (2)

www.flickr.com

www.fnaist.org.uk

www.mirror.co.uk

Return to home page