St

Andrew's Hospital

Dollis Hill Lane, Dollis Hill, NW2 6HD

Medical

dates:

Medical

character:

General

St Andrew's Hospital was

officially opened on 26th September 1913 by Sir David Burnett, the Lord

Mayor of London, at the invitation of the Archbishop of Westminster,

Cardinal Francis Bourne.

The Hospital had been financed by a French benefactress, who wished her name to remain secret during her lifetime. She had contacted the Archbishop and offered a large sum of money for the building of a hospital in the London area. Two of the conditions of the gift were that the nursing care of the hospital should be entrusted to one of the Roman Catholic sisterhoods under the Archbishop, and that these sisters should have received hospital training.

In 1910 a piece of development land at the southern corner of the old Upper Oxgate estate on the crest of Dollis Hill - some 7.25 acres - was acquired for £8,500.

Early in 1913 the central section and the east wing of the Hospital had been completed, and the first patients were admitted in March. The Hospital had cost £50,000 so far - for the land, the building costs and the equipment. When the second wing was completed it would have 100 beds. The Hospital's facade would then be about 300 feet (90 metres) long, facing Dollis Hill Lane.

The 3-storey buildings were built of red brick with Portland stone facings. The two northern corners of the east wing were flanked with towers with dome-shaped roofs (it was intended that the symmetrical west wing could be built at a later date, but this was never realised). The central section contained a ground-floor entrance hall, with a chapel above, surmounted by an octagonal copper dome. The chapel had three altars, which were divided by slender white columns.

Two curving drives ran from the main gate - some 90 yards (83 metres) away - to the Hospital. Letterboxes were set into the iron posts of the main gate to receive 'donations for the Hospital'. Iron railings ran along the length of Dollis Hill Lane, enclosing the Hospital grounds.

The uncompleted Hospital had 63 beds, certain of which were reserved for patients from French-speaking countries. Although under the control of the Archbishop of Westminster and primarily for paying patients of the Roman Catholic faith (the other hospital for this purpose was that of St John and St Elizabeth in St John's Wood), the Hospital was non-sectarian in character and would accept all nationalities. It was intended for middle-class patients who could not afford private nursing home fees, but who were not suitable candidates for admission into charitable institutions. The Order of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God had been appointed to manage the Hospital and provide nursing care. The Sisters had qualified in nursing at the London Hospital and at St George's Hospital.

Some 28 of the beds were for private patients, who paid 7 guineas (£7.35) a week, while 35 were in two main wards (one with 18 beds and one with 17), where patients paid a weekly cost of two and a half guineas (£2.63). The wards were heated by green-tiled, square, open-fire central ventilating stoves, the smoke of which was carried downwards and outwards through flues under the floor. Each stove had a fire on two sides, and a gas-ring in a recess on the other two sides, used for sterilising milk, etc. In addition, parts of the buildings were centrally heated.

The floors and lower walls of the corridors were of terrazzo mosaic, while the cement walls and ceilings were painted with white enamel. The main staircase had been built around a well-protected lift enclosure. One of the automatic electric lifts was large enough to contain a bed, while the other was used to transport food and coal.

The Hospital contained an up-to-date operating theatre (said to have cost £96 and to have come from Berne), dedicated to St Luke - the name was inscribed on the portal - and an anaesthetic room, an X-ray room and a darkroom, a test room, and first-rate sanitary annexes and bathrooms.

A Chaplain's House was built in the east corner of the grounds and there was a coach house for a motor ambulance.

The Hospital had barely been open a year when war broke out in August 1914. Cardinal Bourne immediately offered the Hospital to the British Red Cross Society for the treatment of wounded servicemen. A few days later, Monsignor Maurice Carton de Wiart, the Hospital administrator who was from an illustrious Belgian family, set out with a party of nurses from the Hospital for the village of Hastiere in Belgium. Unfortunately, the village was captured by the Germans from the French on 23rd August (the same day as the Battle of Mons). Sometime later, however, the nurses received medals from the Reconnaisance francaise for their services to wounded French servicemen. The Monsignor himself eventually managed to arrive back in England in the middle of October 1914.

The Hospital became a section of the Second London General Hospital with 70 beds. The Red Cross flag, perforated by bullets at the hospital at Hastiere, flew over the Hospital. Because of its special ability to cope with French-speaking patients, it received wounded soldiers from the French-speaking Belgian army. On 16th October 1914, some 31 Belgians who had been injured during the early fighting were admitted. During the following week the Duke of Vendome visited them and, two days later, Princess Victor Napoleon (a cousin of the King of the Belgians), accompanied by her husband, Prince Victor Napoleon, and the Duchess of Vendome (King Albert's sister).

In 1915 the Order of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God were replaced by another Order, the Sisters of Mercy. In 1917 the Hospital's benefactress died. She was revealed to be Marguerite Amicie Lebaudy (nee Piou).

The Hospital usually celebrated its Founder's Day on 24th May and, on that date in 1917, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir William Dunn, arrived in state with the Lady Mayoress and the Sheriffs to present a cheque to the building fund, the first results of an appeal that Sir William, a member of the Hospital's building committee, had recently launched. The Hospital at that time had only 3 Belgian patients, the rest being from Britain and the Commonwealth.

On Founder's Day in 1918 Queen Alexandra and her daughter, Princess Victoria, visited. Of the Hospital's 90 beds, some 80 were occupied by war-wounded servicemen, including 3 Belgians.

In March 1919 the Hospital was demobilised, but did not celebrate its Founder's Day. During its operational lifetime as a military hospital, it had treated 2,430 troops.

In 1929 the Hospital was enlarged by the addition of another ward block. The men's ward on the ground floor contained 20 beds, and an identical ladies' ward was on the floor above. The top floor of the new block was used for nurses' accommodation until the money could be raised to build a Nurses' Home (the top floor would then be used for patient accommodation). The new wards were cheerful and sunny, with their walls painted in soft greens and blues. The private rooms, each with its own balcony, now cost 8 guineas (£8.40) a week, while a bed in a general ward cost anything from 4 gns (£4.20) down to nothing, depending on the patient's means. These charges included all fees, nursing care and operations.

At the beginning of the 1930s work had begun on the Nurses' Home, which was being built as a British Empire Memorial in memory of King Albert, King of the Belgians. Although only the ground floor had been built by 1935, it was already occupied by probationers. The Home was to be built storey by storey as the fund allowed (some £20,000 was still needed).

The Hospital celebrated its Patronal Day (30th November) each year with a Mass. The Archbishop of Westminster toured the wards and chatted with the patients.

In 1936 the Sisters of Mercy resigned from the management of the Hospital. The Little Company of Mary (the Blue Nuns) agreed to take over.

During the 1930s plastic surgery techniques, mainly for the facial disfigurements of lupus, were pioneered at the Hospital, with Sir Archibald Macindoe, later famous for operating on disfigured airmen at East Grinstead during WW2, as the senior surgeon. The operations were performed in the women's pavilion, which had its own operating theatre. The Plastic Surgery Unit was located in Mary Potter Ward.

In June 1937 a children's ward was opened. It was named after Mgr Carton de Wiart, who had died in 1935 (his body was returned to Belgium for burial in the family vault at Hastiere). An extension was also built to the Nurses' Home, the work for both projects costing £16,356.

The Hospital was disclaimed in 1948 and did not join the NHS.

In 1952 it was enlarged again but, by 1959, it was in financial difficulties, with an overdraft of almost £120,000. The Hospital faced another problem. There were less postulants and fewer Sisters nursing than before, increasing the pressure on some departments, especially for those working in the operating theatre and in the X-ray Department. However, some 75 lay sisters were also employed on the nursing staff. Despite being a Catholic-run Hospital, it was very popular with Jewish patients.

In 1963 another extension was added. The Hospital then had 141 beds, mainly for acute medical and surgical cases. Plans were made for a new operating theatre, a maternity ward and wards with 50 extra beds, at a cost of £300,000.

In 1965, in a fund-raising bid, the Hospital was to benefit from a preview of Twang, a Lionel Bart musical. Unfortunately, the musical was a notorious flop, running only for 43 perfomances before closing.

By 1968 the situation for the Hospital worsened following its amalgamation with the Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth. The motive behind this had been to form a hospital with the 300 beds necessary to ensure continuing recognition of the Nurses Training School. However, the merger proved to be an even greater financial burden and the two Hospitals separated after one year. The General Nursing Council nonetheless continued to treat them as one organisation for nursing purposes, so the Training School continued. In the same year the Blue Nuns left the Hospital, and the uncertain future inevitably affected staff morale.

In 1972 the Hospital was sold to Brent Council, which closed it a year later.

Present status (March 2008)

The Hospital buildings have all been demolished and replaced by housing.

The Hospital gateposts remain.

The Hospital had been financed by a French benefactress, who wished her name to remain secret during her lifetime. She had contacted the Archbishop and offered a large sum of money for the building of a hospital in the London area. Two of the conditions of the gift were that the nursing care of the hospital should be entrusted to one of the Roman Catholic sisterhoods under the Archbishop, and that these sisters should have received hospital training.

In 1910 a piece of development land at the southern corner of the old Upper Oxgate estate on the crest of Dollis Hill - some 7.25 acres - was acquired for £8,500.

Early in 1913 the central section and the east wing of the Hospital had been completed, and the first patients were admitted in March. The Hospital had cost £50,000 so far - for the land, the building costs and the equipment. When the second wing was completed it would have 100 beds. The Hospital's facade would then be about 300 feet (90 metres) long, facing Dollis Hill Lane.

The 3-storey buildings were built of red brick with Portland stone facings. The two northern corners of the east wing were flanked with towers with dome-shaped roofs (it was intended that the symmetrical west wing could be built at a later date, but this was never realised). The central section contained a ground-floor entrance hall, with a chapel above, surmounted by an octagonal copper dome. The chapel had three altars, which were divided by slender white columns.

Two curving drives ran from the main gate - some 90 yards (83 metres) away - to the Hospital. Letterboxes were set into the iron posts of the main gate to receive 'donations for the Hospital'. Iron railings ran along the length of Dollis Hill Lane, enclosing the Hospital grounds.

The uncompleted Hospital had 63 beds, certain of which were reserved for patients from French-speaking countries. Although under the control of the Archbishop of Westminster and primarily for paying patients of the Roman Catholic faith (the other hospital for this purpose was that of St John and St Elizabeth in St John's Wood), the Hospital was non-sectarian in character and would accept all nationalities. It was intended for middle-class patients who could not afford private nursing home fees, but who were not suitable candidates for admission into charitable institutions. The Order of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God had been appointed to manage the Hospital and provide nursing care. The Sisters had qualified in nursing at the London Hospital and at St George's Hospital.

Some 28 of the beds were for private patients, who paid 7 guineas (£7.35) a week, while 35 were in two main wards (one with 18 beds and one with 17), where patients paid a weekly cost of two and a half guineas (£2.63). The wards were heated by green-tiled, square, open-fire central ventilating stoves, the smoke of which was carried downwards and outwards through flues under the floor. Each stove had a fire on two sides, and a gas-ring in a recess on the other two sides, used for sterilising milk, etc. In addition, parts of the buildings were centrally heated.

The floors and lower walls of the corridors were of terrazzo mosaic, while the cement walls and ceilings were painted with white enamel. The main staircase had been built around a well-protected lift enclosure. One of the automatic electric lifts was large enough to contain a bed, while the other was used to transport food and coal.

The Hospital contained an up-to-date operating theatre (said to have cost £96 and to have come from Berne), dedicated to St Luke - the name was inscribed on the portal - and an anaesthetic room, an X-ray room and a darkroom, a test room, and first-rate sanitary annexes and bathrooms.

A Chaplain's House was built in the east corner of the grounds and there was a coach house for a motor ambulance.

The Hospital had barely been open a year when war broke out in August 1914. Cardinal Bourne immediately offered the Hospital to the British Red Cross Society for the treatment of wounded servicemen. A few days later, Monsignor Maurice Carton de Wiart, the Hospital administrator who was from an illustrious Belgian family, set out with a party of nurses from the Hospital for the village of Hastiere in Belgium. Unfortunately, the village was captured by the Germans from the French on 23rd August (the same day as the Battle of Mons). Sometime later, however, the nurses received medals from the Reconnaisance francaise for their services to wounded French servicemen. The Monsignor himself eventually managed to arrive back in England in the middle of October 1914.

The Hospital became a section of the Second London General Hospital with 70 beds. The Red Cross flag, perforated by bullets at the hospital at Hastiere, flew over the Hospital. Because of its special ability to cope with French-speaking patients, it received wounded soldiers from the French-speaking Belgian army. On 16th October 1914, some 31 Belgians who had been injured during the early fighting were admitted. During the following week the Duke of Vendome visited them and, two days later, Princess Victor Napoleon (a cousin of the King of the Belgians), accompanied by her husband, Prince Victor Napoleon, and the Duchess of Vendome (King Albert's sister).

In 1915 the Order of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God were replaced by another Order, the Sisters of Mercy. In 1917 the Hospital's benefactress died. She was revealed to be Marguerite Amicie Lebaudy (nee Piou).

The Hospital usually celebrated its Founder's Day on 24th May and, on that date in 1917, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir William Dunn, arrived in state with the Lady Mayoress and the Sheriffs to present a cheque to the building fund, the first results of an appeal that Sir William, a member of the Hospital's building committee, had recently launched. The Hospital at that time had only 3 Belgian patients, the rest being from Britain and the Commonwealth.

On Founder's Day in 1918 Queen Alexandra and her daughter, Princess Victoria, visited. Of the Hospital's 90 beds, some 80 were occupied by war-wounded servicemen, including 3 Belgians.

In March 1919 the Hospital was demobilised, but did not celebrate its Founder's Day. During its operational lifetime as a military hospital, it had treated 2,430 troops.

In 1929 the Hospital was enlarged by the addition of another ward block. The men's ward on the ground floor contained 20 beds, and an identical ladies' ward was on the floor above. The top floor of the new block was used for nurses' accommodation until the money could be raised to build a Nurses' Home (the top floor would then be used for patient accommodation). The new wards were cheerful and sunny, with their walls painted in soft greens and blues. The private rooms, each with its own balcony, now cost 8 guineas (£8.40) a week, while a bed in a general ward cost anything from 4 gns (£4.20) down to nothing, depending on the patient's means. These charges included all fees, nursing care and operations.

At the beginning of the 1930s work had begun on the Nurses' Home, which was being built as a British Empire Memorial in memory of King Albert, King of the Belgians. Although only the ground floor had been built by 1935, it was already occupied by probationers. The Home was to be built storey by storey as the fund allowed (some £20,000 was still needed).

The Hospital celebrated its Patronal Day (30th November) each year with a Mass. The Archbishop of Westminster toured the wards and chatted with the patients.

In 1936 the Sisters of Mercy resigned from the management of the Hospital. The Little Company of Mary (the Blue Nuns) agreed to take over.

During the 1930s plastic surgery techniques, mainly for the facial disfigurements of lupus, were pioneered at the Hospital, with Sir Archibald Macindoe, later famous for operating on disfigured airmen at East Grinstead during WW2, as the senior surgeon. The operations were performed in the women's pavilion, which had its own operating theatre. The Plastic Surgery Unit was located in Mary Potter Ward.

In June 1937 a children's ward was opened. It was named after Mgr Carton de Wiart, who had died in 1935 (his body was returned to Belgium for burial in the family vault at Hastiere). An extension was also built to the Nurses' Home, the work for both projects costing £16,356.

The Hospital was disclaimed in 1948 and did not join the NHS.

In 1952 it was enlarged again but, by 1959, it was in financial difficulties, with an overdraft of almost £120,000. The Hospital faced another problem. There were less postulants and fewer Sisters nursing than before, increasing the pressure on some departments, especially for those working in the operating theatre and in the X-ray Department. However, some 75 lay sisters were also employed on the nursing staff. Despite being a Catholic-run Hospital, it was very popular with Jewish patients.

In 1963 another extension was added. The Hospital then had 141 beds, mainly for acute medical and surgical cases. Plans were made for a new operating theatre, a maternity ward and wards with 50 extra beds, at a cost of £300,000.

In 1965, in a fund-raising bid, the Hospital was to benefit from a preview of Twang, a Lionel Bart musical. Unfortunately, the musical was a notorious flop, running only for 43 perfomances before closing.

By 1968 the situation for the Hospital worsened following its amalgamation with the Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth. The motive behind this had been to form a hospital with the 300 beds necessary to ensure continuing recognition of the Nurses Training School. However, the merger proved to be an even greater financial burden and the two Hospitals separated after one year. The General Nursing Council nonetheless continued to treat them as one organisation for nursing purposes, so the Training School continued. In the same year the Blue Nuns left the Hospital, and the uncertain future inevitably affected staff morale.

In 1972 the Hospital was sold to Brent Council, which closed it a year later.

Present status (March 2008)

The Hospital buildings have all been demolished and replaced by housing.

The Hospital gateposts remain.

Pippin Close, off Dollis Hill Lane, was once the main driveway to the Hospital (left). The top of Pippin Close occupies part of the site of the Hospital (right).

The old gateposts for the Hospital remain, located on either side of Pippin Close.

The gateposts had letterboxes set into them so that people could post donations to the Hospital.

The gates either side of St Mary's and St Andrew's Church still retain the 1911 iron gateposts. (The house on the left is the Church presbytery.)

The left-hand gateposts are inscribed '19' and the right-hand ones '11'.

The Roman Catholic Church of St Mary and St Andrew on Dollis Hill Lane. In 1913 the Catholics of the area could attend Mass in the Hospital chapel but, with increasing numbers, a wooden church was built in the Hospital grounds. In November 1927 the Rosminian Fathers were invited by the Archbishop of Westminster to begin the Parish of St Mary and St Andrew. As the congregation continued to increase, a new church was built in the southwest corner of Hospital grounds. It opened on 18th May, 1933.

The entrance to Newfield Rise, part of the St Andrew's Estate (left), built on the northern part of the Hospital grounds. The southern part of Newfield Rise (right).

Comber Close, also built on the northern portion of the Hospital grounds (left). A wall built using old bricks, perhaps once part of the Hospital (right).

St Mary's

Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green

During WW1 Mgr Carton de Wiart, the Hospital administrator, acquired a plot of land in St Mary's Cemetary in which to bury the Belgian soldiers who had died at the Hospital.

In 1923 some 75 bodies were removed to Zeebrugge on the cruiser Calliope and then transported to their native towns and villages for burial. The remaining 77 stayed in the cemetery plot.

The Belgian Soldiers' Memorial at the northeast corner of the Cemetery was unveiled in 1932 by the Belgian Ambassador, Baron de Cartier de Marchienne. The names of the 77 men are carved on the memorial.

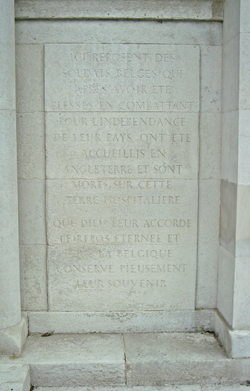

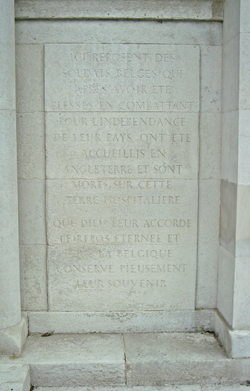

The central Pieta, sculpted by Philip Lindsey Clark (1889-1977) in conjunction with Sue Dring, is flanked by stone panels in French and Flemish.

The stone panel on the right is in French and the one on the left in Flemish.

A tablet is set into the paved area in front of the memorial . It reads "A nous le souvenir a eux l'immortalitie oeuvre nationale le souvenir Belge 1914-1918" (For us the memory, for them immortality. Remember the Belgian national struggle, 1914-1918).

The Cemetery also contains a Canadian (and Allied) War Memorial at the southwest corner.

The memorial is flanked by gravestones on the right (below right) and numbered markers set in the lawn on the left (below left).

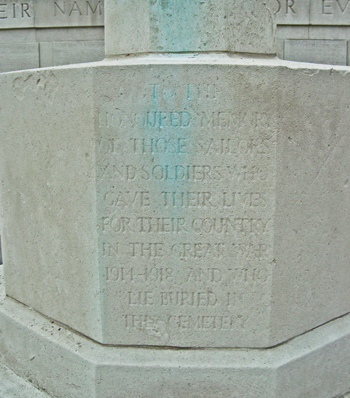

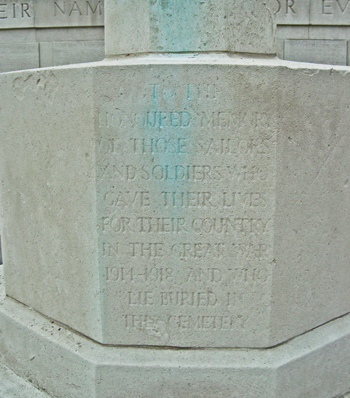

The central cross and the wall behind commemorate the dead of WW1. The two low walls in front of the memorial were added after WW2.

The dedication under the cross.

During WW1 Mgr Carton de Wiart, the Hospital administrator, acquired a plot of land in St Mary's Cemetary in which to bury the Belgian soldiers who had died at the Hospital.

In 1923 some 75 bodies were removed to Zeebrugge on the cruiser Calliope and then transported to their native towns and villages for burial. The remaining 77 stayed in the cemetery plot.

The Belgian Soldiers' Memorial at the northeast corner of the Cemetery was unveiled in 1932 by the Belgian Ambassador, Baron de Cartier de Marchienne. The names of the 77 men are carved on the memorial.

The central Pieta, sculpted by Philip Lindsey Clark (1889-1977) in conjunction with Sue Dring, is flanked by stone panels in French and Flemish.

The stone panel on the right is in French and the one on the left in Flemish.

A tablet is set into the paved area in front of the memorial . It reads "A nous le souvenir a eux l'immortalitie oeuvre nationale le souvenir Belge 1914-1918" (For us the memory, for them immortality. Remember the Belgian national struggle, 1914-1918).

The Cemetery also contains a Canadian (and Allied) War Memorial at the southwest corner.

The memorial is flanked by gravestones on the right (below right) and numbered markers set in the lawn on the left (below left).

The central cross and the wall behind commemorate the dead of WW1. The two low walls in front of the memorial were added after WW2.

The dedication under the cross.

(Author unstated) 1912 St Andrew's Hospital. British Journal of Nursing, 23rd November, 416.

(Author unstated) 1913 A new hospital for paying patients. British Journal of Nursing, 4th October, 277.

(Author unstated) 1914 The care of the wounded. British Journal of Nursing, 31st October, 347.

(Author unstated) 1917 List of the various hospitals treating military cases in the United Kingdom. London, H.M.S.O.

(Author unstated) 1934 Memorial to the late King Albert. British Journal of Nursing (November), 306.

(Author unstated) 1935 British Empire memorial to King of the Belgians. British Journal of Nursing (March), 77.

Fenn CR 1919 Middlesex to Wit. London, St Catherine Press.

Hawkins H 1935 St Andrew's Hospital, Dolllis Hill. British Journal of Nursing (April), 90-91.

Valentine K 1983 The Founding of Saint Andrew's Hospital, Dollis Hill. London, Willesden Local History Society.

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1935)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1937)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1936)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1959)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (Feb 1960)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (Oct 1960)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1963)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1965)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1968)

http://archive.catholicherald.co.uk (1971)

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com

http://viewfinder.english-heritage.co.uk

www.british-history.ac.uk (1)

www.british-history.ac.uk (2)

www.britishpathe.com

www.flickr.com (1)

www.flickr.com (2)

www.flickr.com (3)

www.flickr.com (4)

www.flickr.com (5)

www.gettyimages.co.uk

www.images-of-london.co.uk (1)

www.images-of-london.co.uk (2)

www.photo-canvas.com

Return to home page