Middlesex

Hospital

Mortimer Street, W1T 3PW

Medical

dates:

Medical

character:

Acute

(Teaching Hospital)

The Middlesex

Infirmary 'for the Sick and Lame of Soho' opened in 1745, named after

the county it stood in (the county of London did not exist until 1888).

Founded

by 20 benefactors, it consisted of 15 beds in two houses - Nos. 8-10

Windmill

Street - leased from Mr. Goodge, built on a site which had once been a

home for 40 lepers until

closed down by Henry VIII.

Soho, and its neighbouring parish St

Giles, was a thickly populated area at this time, where the inhabitants

lived in dire poverty; four out of five of these were scarred by

smallpox,

endemic at the time.

The Infirmary managed to attract subscribers, who paid 3 gns (£3.15) a year or 21 gns (£22.05) for life membership. However, within a year of opening, the committee sacked the paid staff, including the Matron and the apothecary, for "indecencies and irregularities" (the apothecary's actions were described as "vile and enormous"). It survived this and other crises, mainly financial, and , in 1747, was the first hospital in England to provide 'lying-in' beds for pregnant women. A sign was placed at the end of the street stating 'The Middlesex Hospital for Sick and Lame and Lying-In Married Women'. The number of beds increased to 25 - four of which were reserved for accident cases, 10 for the sick and lame and 10 for lying-in patients. (Later, one of the two staff doctors plotted to change it to a purely lying-in hospital, and was also dismissed. A number of staff members resigned. The President, the Duke of Portland, also resigned.) Demand for beds continued and some patients had to be accommodated in neighbouring houses. The Hospital had 40 beds, but the Matron thought it "undesirable that there should be two in a bed as sometimes was found necessary".

The Hospital Governors decided that the premises were inadequate and a new site was found in Marylebone Fields, on the estate of Mr Charles Berners. A lease was signed for 999 years at a rent of £15 per annum and, in May 1755, the new President of the Hospital, the Earl of Northumberland, laid the foundation stone of the new building.

In 1757 the Hospital moved to its purpose-built premises in Mortimer Street, which had cost £2,250 to build. Only the central block had been built (the two wings were added later). It had 64 beds and a separate maternity wing with 34 beds. Mortimer Street then was at the extreme edge of London, separated from Tottenham Court Road by marshland ("a good place for snipe-shooting").

The east and west wings were gradually added in 1766 and 1780 but the latter could not be occupied because of lack of funds (the maternity ward had shrunk to 2 beds).

In 1791 the brewer Samuel Whitbread bequeathed £3,000 to endow a ward for cancer patients and, in 1815, a ward was named after him and was one of the reasons why the Hospital was at the forefront in the treatment and research of cancer.

Another financial crisis was precipitated by the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars in 1793. Many of the wards lay empty and the nurses threatened to strike when their food and beer allowances were reduced to save money (this was resolved when rice was added to their diet). In 1796 the Hospital was asked if it would open a ward for sick French clergy, who were refugees from the Revolution. Thus, the first paying patients were admitted. They filled two wards and were charged 8s (40p) a week, exclusive of bedding and nurses' wages. During one year some 340 were admitted, of whom 109 died. The arrangement remained in place for 20 years and the last patients finally departed in August 1814. In 1815, the year of the battle of Waterloo, the Hospital had 179 beds.

By 1848, following extension of the wings to the street and adding a third floor, the Hospital had 240 beds.

During the cholera outbreak of 1854 the Hospital was overwhelmed with the sick, dying and dead. Florence Nightingale offered her help.

By the end of the century, the Hospital was again in financial difficulties and £10,000 of railway stock had to be sold to avert the alternative of closing wards (although wards were closed to new admission for eight weeks during the summer in 1899).

In 1910 new maternity wards opened, replacing the 10-bedded ward opened in 1908. One of the new wards contained six beds and the other four. Cots for the infants were slung at the foot of each bed. Bathrooms in the wards enabled patients to be bathed and clothed in clean clothes before entering the labour ward, which was like a small operating theatre equipped with every appliance and instrument likely to be necessary.

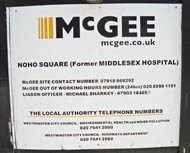

At the beginning of April 1912 a new cancer wing was officially opened by Queen Mary. It was named the Barnato-Joel Wing, after the late Henry Barnato, who had left £250,000 for the foundation of a hospital in memory of his brother Barney and his nephew Woolf Joel (the money was given to the Hospital to further its research work). The new wing had a frontage of 90 ft in Nassau Street. It had 43 beds and, if necessary, patients were allowed to remain until "'Death the Consoler' had healed them for ever and ever". The building also contained an Out-Patients Department with a waiting hall with seats for 115 people, an Electrical Department where massage was also given, a state-of-the-art operating theatre and a Home for 59 nurses (each had a single bedroom) and 23 servants. There was a classroom for pupil nurses and, in addition to the general kitchen, a special kitchen where food for Jewish patients could be prepared in accordance with the rules of their religion. In the basement there was a room devoted to the scrubbers; each had a locker where she could keep her special implements of work (Matron was of the opinion that too little consideration was often given to the needs of the scrubbers in this respect).

During WW1 some 60 beds of the Hospital were reserved for sick or injured servicemen as a section of the Third London General Hospital.

By 1924 the main 18th century hospital building was in danger of collapsing and a Dangerous Structure notice was served. The Cleveland Street Infirmary was taken over as an annexe in 1926 (it later became the Out-Patients Department) and in-patients were moved there while the Hospital was demolished in stages and entirely rebuilt on the same site, without once closing its doors to patients.

In July 1927 the foundation stone was laid for a new Institute of Biochemistry. The money needed for this had been donated by Samuel Augustine Courtauld, a descendant of a Huguenot refugee from France, who had been a subscriber in 1748 to the original Hospital. The Institute opened the following year.

In January 1929 the Queen laid the foundation stone for a new Nurses' Home in Foley Street, made possible by an anonymous gift of £300,000. The Home, or rather Residential College for Nurses, was opened by Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, in June 1931. It provided accommodation for 300 people - 230 Sisters and Nurses, pupils of the Preliminary Training School, as well as those attending Massage and Midwifery courses, and domestic staff. The building also contained the Preliminary Training School and its classrooms, recreation and smoking rooms, badminton and tennis courts and, in the basement, a swimming pool (only to be used when at least three people were present, two of whom had to be good swimmers). The oak-panelled dining room was on the ground floor and the kitchen was capable of supplying meals for 300 people at one sitting. There was also a hairdressing salon in the basement. (It was later renamed John Astor House, after the anonymous donor was identified in 1948 when the Hospital joined the NHS).

A children's ward opened in 1930 on the sixth floor of the new West Wing, which had been completed in 1929. The cots were bright blue. The walls of the ward were faced with tiles illustrating nursery rhymes, which had been donated by Bernhard Baron, who had also given £10,000 to the Hospital. The ward had its own kitchen and a sun balcony. Newly admitted patients were accommodated in isolation rooms, which were separated by glass panels, for three of four days until a clear medical history had been obtained.

In January 1934 an explosion occurred in the main ground floor theatre as the dispensary porter was changing the reducing valve on a large oxygen cylinder in the anaesthetic room. The issuing oxygen caused a fire, and a 15 ft stream of sparks and flames shot through the open door into the theatre. The theatre was immediately evacuated but the Theatre Sister remained behind to remove the ether from the anaesthetic room and closed the doors to minimise the effect of any further explosion. However, she swiftly decided that it was her duty to avert the destruction of the theatre and re-entered the anaesthetic room to turn off the oxygen cylinder. She was awarded the Medal of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire for this gallantry.

The Crosspiece and the East Wing were completed in 1935 and the new building was officially opened in June by the Duke of York (who later became King George VI). The Hospital had 712 beds and had cost £1,125,000 to rebuild, entirely paid for by donations - some large and some small (one milliner in Oxford Street had collected 5,000 farthings - about £5.21). It had seven storeys and was built to the same style, with projecting wings and a crosspiece. Even the clock was replaced in the pediment, now with a gold face instead of a plain one. The entrance hall was panelled with paintings representing Acts of Mercy by Frederick Cayley Robinson. Beyond the hall was a terrace which led to an open courtyard, surrounded on its four sides by the Hospital.

The main X-ray Department, gifted by Mr. W.H. Collins, a London businessman, began working the same day as the Hospital's opening. A Radiotherapy Department, the gift of Mr E.W. Meyerstein, a retired stockbroker, was almost complete. Both benefactors gave a further £50,000 each to endow these departments. Mr Stafford Bourne, one of the founders of the department store Bourne and Hollingsworth, donated the funds for an operating theatre, which subsequently bore his name. A new Fracture Unit was planned.

A block for private patients was made possible by the Canadian-born Lord Woolavington, who donated a large sum of money for this purpose in memory of his wife who had died in 1918. At this time patients could only be admitted if their income was below certain strict levels. Middle-class patients therefore could only be treated in nursing homes, which were expensive and not very well equipped. The Hospital Board decided to convert the residents' block in Cleveland Street, built in 1887, and the Sisters' Home, built a few years later, into a private wing and to build new premises for the resident house staff. The Woolavington Private Wing opened in 1934.

During WW2 the top three floors of the Hospital were emptied of patients for safety reasons and, in fact, were damaged by bombs. As a teaching hospital, the Hospital was in charge of one of the sectors of the Emergency Medical Service, with its advanced base hospital at Mount Vernon Hospital.

In 1948 the Middlesex Hospital joined the NHS and became the lead hospital in a teaching hospital group which included its convalescent home at Clacton-on Sea, the Hospital for Women in Soho, St. Luke's-Woodside (a psychiatric hospital in Muswell Hill) and the Arthur Stanley Institute for Rheumatic Diseases (previously the British Red Cross Clinic for Rheumatism). In 1958 the Hospital acquired Caen Wood Towers in Highgate for use as a post-operative recovery and geriatric unit (its name was changed to Athlone House, after the Earl of Athlone, a former Chairman of the Board of Governors).

In 1980, following a reorganisation of the NHS, the Hospital together with University College Hospital and several smaller specialist hospitals in the area came under the control of the Bloomsbury Health District.

In 1984 the in-patients building of the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in Great Portland Street closed and services moved to an upgraded ward on the fifth floor of the Middlesex Hospital.

In 1987 Broderip and Charles Bell Wards, the first in the United Kingdom dedicated to the treatment and care of patients with AIDS and HIV-related illnesses, were opened by Princess Diana.

In 1992 the urology hospitals - the 3 Ps (St Paul's, St Peter's and St Philip's) - closed and moved their services into newly refurbished ward accommodation at the Middlesex Hospital.

The Hospital closed in 2006 and all services moved to the new £422m PFI-built University College Hospital (UCH) in Euston Road. The 16-storey tower there has been named the Middlesex Tower in honour of the Hospital.

The Infirmary managed to attract subscribers, who paid 3 gns (£3.15) a year or 21 gns (£22.05) for life membership. However, within a year of opening, the committee sacked the paid staff, including the Matron and the apothecary, for "indecencies and irregularities" (the apothecary's actions were described as "vile and enormous"). It survived this and other crises, mainly financial, and , in 1747, was the first hospital in England to provide 'lying-in' beds for pregnant women. A sign was placed at the end of the street stating 'The Middlesex Hospital for Sick and Lame and Lying-In Married Women'. The number of beds increased to 25 - four of which were reserved for accident cases, 10 for the sick and lame and 10 for lying-in patients. (Later, one of the two staff doctors plotted to change it to a purely lying-in hospital, and was also dismissed. A number of staff members resigned. The President, the Duke of Portland, also resigned.) Demand for beds continued and some patients had to be accommodated in neighbouring houses. The Hospital had 40 beds, but the Matron thought it "undesirable that there should be two in a bed as sometimes was found necessary".

The Hospital Governors decided that the premises were inadequate and a new site was found in Marylebone Fields, on the estate of Mr Charles Berners. A lease was signed for 999 years at a rent of £15 per annum and, in May 1755, the new President of the Hospital, the Earl of Northumberland, laid the foundation stone of the new building.

In 1757 the Hospital moved to its purpose-built premises in Mortimer Street, which had cost £2,250 to build. Only the central block had been built (the two wings were added later). It had 64 beds and a separate maternity wing with 34 beds. Mortimer Street then was at the extreme edge of London, separated from Tottenham Court Road by marshland ("a good place for snipe-shooting").

The east and west wings were gradually added in 1766 and 1780 but the latter could not be occupied because of lack of funds (the maternity ward had shrunk to 2 beds).

In 1791 the brewer Samuel Whitbread bequeathed £3,000 to endow a ward for cancer patients and, in 1815, a ward was named after him and was one of the reasons why the Hospital was at the forefront in the treatment and research of cancer.

Another financial crisis was precipitated by the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars in 1793. Many of the wards lay empty and the nurses threatened to strike when their food and beer allowances were reduced to save money (this was resolved when rice was added to their diet). In 1796 the Hospital was asked if it would open a ward for sick French clergy, who were refugees from the Revolution. Thus, the first paying patients were admitted. They filled two wards and were charged 8s (40p) a week, exclusive of bedding and nurses' wages. During one year some 340 were admitted, of whom 109 died. The arrangement remained in place for 20 years and the last patients finally departed in August 1814. In 1815, the year of the battle of Waterloo, the Hospital had 179 beds.

By 1848, following extension of the wings to the street and adding a third floor, the Hospital had 240 beds.

During the cholera outbreak of 1854 the Hospital was overwhelmed with the sick, dying and dead. Florence Nightingale offered her help.

By the end of the century, the Hospital was again in financial difficulties and £10,000 of railway stock had to be sold to avert the alternative of closing wards (although wards were closed to new admission for eight weeks during the summer in 1899).

In 1910 new maternity wards opened, replacing the 10-bedded ward opened in 1908. One of the new wards contained six beds and the other four. Cots for the infants were slung at the foot of each bed. Bathrooms in the wards enabled patients to be bathed and clothed in clean clothes before entering the labour ward, which was like a small operating theatre equipped with every appliance and instrument likely to be necessary.

At the beginning of April 1912 a new cancer wing was officially opened by Queen Mary. It was named the Barnato-Joel Wing, after the late Henry Barnato, who had left £250,000 for the foundation of a hospital in memory of his brother Barney and his nephew Woolf Joel (the money was given to the Hospital to further its research work). The new wing had a frontage of 90 ft in Nassau Street. It had 43 beds and, if necessary, patients were allowed to remain until "'Death the Consoler' had healed them for ever and ever". The building also contained an Out-Patients Department with a waiting hall with seats for 115 people, an Electrical Department where massage was also given, a state-of-the-art operating theatre and a Home for 59 nurses (each had a single bedroom) and 23 servants. There was a classroom for pupil nurses and, in addition to the general kitchen, a special kitchen where food for Jewish patients could be prepared in accordance with the rules of their religion. In the basement there was a room devoted to the scrubbers; each had a locker where she could keep her special implements of work (Matron was of the opinion that too little consideration was often given to the needs of the scrubbers in this respect).

During WW1 some 60 beds of the Hospital were reserved for sick or injured servicemen as a section of the Third London General Hospital.

By 1924 the main 18th century hospital building was in danger of collapsing and a Dangerous Structure notice was served. The Cleveland Street Infirmary was taken over as an annexe in 1926 (it later became the Out-Patients Department) and in-patients were moved there while the Hospital was demolished in stages and entirely rebuilt on the same site, without once closing its doors to patients.

In July 1927 the foundation stone was laid for a new Institute of Biochemistry. The money needed for this had been donated by Samuel Augustine Courtauld, a descendant of a Huguenot refugee from France, who had been a subscriber in 1748 to the original Hospital. The Institute opened the following year.

In January 1929 the Queen laid the foundation stone for a new Nurses' Home in Foley Street, made possible by an anonymous gift of £300,000. The Home, or rather Residential College for Nurses, was opened by Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, in June 1931. It provided accommodation for 300 people - 230 Sisters and Nurses, pupils of the Preliminary Training School, as well as those attending Massage and Midwifery courses, and domestic staff. The building also contained the Preliminary Training School and its classrooms, recreation and smoking rooms, badminton and tennis courts and, in the basement, a swimming pool (only to be used when at least three people were present, two of whom had to be good swimmers). The oak-panelled dining room was on the ground floor and the kitchen was capable of supplying meals for 300 people at one sitting. There was also a hairdressing salon in the basement. (It was later renamed John Astor House, after the anonymous donor was identified in 1948 when the Hospital joined the NHS).

A children's ward opened in 1930 on the sixth floor of the new West Wing, which had been completed in 1929. The cots were bright blue. The walls of the ward were faced with tiles illustrating nursery rhymes, which had been donated by Bernhard Baron, who had also given £10,000 to the Hospital. The ward had its own kitchen and a sun balcony. Newly admitted patients were accommodated in isolation rooms, which were separated by glass panels, for three of four days until a clear medical history had been obtained.

In January 1934 an explosion occurred in the main ground floor theatre as the dispensary porter was changing the reducing valve on a large oxygen cylinder in the anaesthetic room. The issuing oxygen caused a fire, and a 15 ft stream of sparks and flames shot through the open door into the theatre. The theatre was immediately evacuated but the Theatre Sister remained behind to remove the ether from the anaesthetic room and closed the doors to minimise the effect of any further explosion. However, she swiftly decided that it was her duty to avert the destruction of the theatre and re-entered the anaesthetic room to turn off the oxygen cylinder. She was awarded the Medal of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire for this gallantry.

The Crosspiece and the East Wing were completed in 1935 and the new building was officially opened in June by the Duke of York (who later became King George VI). The Hospital had 712 beds and had cost £1,125,000 to rebuild, entirely paid for by donations - some large and some small (one milliner in Oxford Street had collected 5,000 farthings - about £5.21). It had seven storeys and was built to the same style, with projecting wings and a crosspiece. Even the clock was replaced in the pediment, now with a gold face instead of a plain one. The entrance hall was panelled with paintings representing Acts of Mercy by Frederick Cayley Robinson. Beyond the hall was a terrace which led to an open courtyard, surrounded on its four sides by the Hospital.

The main X-ray Department, gifted by Mr. W.H. Collins, a London businessman, began working the same day as the Hospital's opening. A Radiotherapy Department, the gift of Mr E.W. Meyerstein, a retired stockbroker, was almost complete. Both benefactors gave a further £50,000 each to endow these departments. Mr Stafford Bourne, one of the founders of the department store Bourne and Hollingsworth, donated the funds for an operating theatre, which subsequently bore his name. A new Fracture Unit was planned.

A block for private patients was made possible by the Canadian-born Lord Woolavington, who donated a large sum of money for this purpose in memory of his wife who had died in 1918. At this time patients could only be admitted if their income was below certain strict levels. Middle-class patients therefore could only be treated in nursing homes, which were expensive and not very well equipped. The Hospital Board decided to convert the residents' block in Cleveland Street, built in 1887, and the Sisters' Home, built a few years later, into a private wing and to build new premises for the resident house staff. The Woolavington Private Wing opened in 1934.

During WW2 the top three floors of the Hospital were emptied of patients for safety reasons and, in fact, were damaged by bombs. As a teaching hospital, the Hospital was in charge of one of the sectors of the Emergency Medical Service, with its advanced base hospital at Mount Vernon Hospital.

In 1948 the Middlesex Hospital joined the NHS and became the lead hospital in a teaching hospital group which included its convalescent home at Clacton-on Sea, the Hospital for Women in Soho, St. Luke's-Woodside (a psychiatric hospital in Muswell Hill) and the Arthur Stanley Institute for Rheumatic Diseases (previously the British Red Cross Clinic for Rheumatism). In 1958 the Hospital acquired Caen Wood Towers in Highgate for use as a post-operative recovery and geriatric unit (its name was changed to Athlone House, after the Earl of Athlone, a former Chairman of the Board of Governors).

In 1980, following a reorganisation of the NHS, the Hospital together with University College Hospital and several smaller specialist hospitals in the area came under the control of the Bloomsbury Health District.

In 1984 the in-patients building of the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital in Great Portland Street closed and services moved to an upgraded ward on the fifth floor of the Middlesex Hospital.

In 1987 Broderip and Charles Bell Wards, the first in the United Kingdom dedicated to the treatment and care of patients with AIDS and HIV-related illnesses, were opened by Princess Diana.

In 1992 the urology hospitals - the 3 Ps (St Paul's, St Peter's and St Philip's) - closed and moved their services into newly refurbished ward accommodation at the Middlesex Hospital.

The Hospital closed in 2006 and all services moved to the new £422m PFI-built University College Hospital (UCH) in Euston Road. The 16-storey tower there has been named the Middlesex Tower in honour of the Hospital.

Present status (September

2010)

UCH attempted to sell off the 'Acts of Mercy' mural paintings by the Symbolist painter Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862-1927) claiming that 'there was no room for them' in the new UCH building. This caused great public outcry. The paintings, commissioned by Sir Edmund Davis in 1910 for the previous Middlesex Hospital building, had been presented to the Hospital in 1919. When the Hospital was rebuilt, the paintings were sited in the front entrance area. The paintings were eventually bought by the Wellcome Trust and displayed in the Wellcome Library in Euston Road (they are currently on exhibition in the National Gallery).

In 2006 the 2.97 acre (1.2 ha) site of prime real estate was bought for £175m by the offshore consortium Project Abbey (Guernsey), of which the CPC Group, owned by Christian Candy, was the principal shareholder, together with the Icelandic bank Kaupthing. Candy & Candy, luxury residential developers, would act as development managers and interior designers for the redevelopment of the site.

Most of the Hospital was demolished in 2008. The Grade II listed chapel, built in 1891 in Italian Gothic style, was retained, as well as the Arts and Crafts building at 10 Mortimer Street.

The development was to have included 261 luxury apartments as well as restaurants, shops and offices - and a public square in the centre. The project was called Noho Square. (The locals did not approve and dubbed it Nono Square, even altering the 'h' to an 'n' on the advertising boards). Construction was due to start in the summer of 2008 and be completed by early 2011.

However, following the banking crisis of 2008 the deal fell through and the Candy brothers gave the site to the collapsed bank Kaupthing. As the site was likely to remain vacant for some time, the local residents, led by Cllr Rebecca Hossack, requested that they use it for temporary allotments. Having agreed to this idea in principle, the bank's Chairman then reneged in March 2010 and announced the site would be put on the market.

In August 2010 the site was sold to Aviva Investors and Exemplar Properties.

UPDATE: January 2016

The new development has been named Fitzroy Place and is now completed. Little remains of the original Hospital - only the front elevation of the Radium Wing along Nassau Street, which has been incorporated into the new building, and the Hospital chapel, which has been beautifully restored.

The chapel has been renamed Fitzrovia Chapel, despite vociferous protests from former staff and local residents to allow it to keep its old name. The unconsecrated chapel will be used for community events in the future, but is currently open to the public on Wednesdays from 11.00 till 16.00. It is entered by a side door on the eastern side.

UCH attempted to sell off the 'Acts of Mercy' mural paintings by the Symbolist painter Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862-1927) claiming that 'there was no room for them' in the new UCH building. This caused great public outcry. The paintings, commissioned by Sir Edmund Davis in 1910 for the previous Middlesex Hospital building, had been presented to the Hospital in 1919. When the Hospital was rebuilt, the paintings were sited in the front entrance area. The paintings were eventually bought by the Wellcome Trust and displayed in the Wellcome Library in Euston Road (they are currently on exhibition in the National Gallery).

In 2006 the 2.97 acre (1.2 ha) site of prime real estate was bought for £175m by the offshore consortium Project Abbey (Guernsey), of which the CPC Group, owned by Christian Candy, was the principal shareholder, together with the Icelandic bank Kaupthing. Candy & Candy, luxury residential developers, would act as development managers and interior designers for the redevelopment of the site.

Most of the Hospital was demolished in 2008. The Grade II listed chapel, built in 1891 in Italian Gothic style, was retained, as well as the Arts and Crafts building at 10 Mortimer Street.

The development was to have included 261 luxury apartments as well as restaurants, shops and offices - and a public square in the centre. The project was called Noho Square. (The locals did not approve and dubbed it Nono Square, even altering the 'h' to an 'n' on the advertising boards). Construction was due to start in the summer of 2008 and be completed by early 2011.

However, following the banking crisis of 2008 the deal fell through and the Candy brothers gave the site to the collapsed bank Kaupthing. As the site was likely to remain vacant for some time, the local residents, led by Cllr Rebecca Hossack, requested that they use it for temporary allotments. Having agreed to this idea in principle, the bank's Chairman then reneged in March 2010 and announced the site would be put on the market.

In August 2010 the site was sold to Aviva Investors and Exemplar Properties.

UPDATE: January 2016

The new development has been named Fitzroy Place and is now completed. Little remains of the original Hospital - only the front elevation of the Radium Wing along Nassau Street, which has been incorporated into the new building, and the Hospital chapel, which has been beautifully restored.

The chapel has been renamed Fitzrovia Chapel, despite vociferous protests from former staff and local residents to allow it to keep its old name. The unconsecrated chapel will be used for community events in the future, but is currently open to the public on Wednesdays from 11.00 till 16.00. It is entered by a side door on the eastern side.

N.B. Photographs

obtained in 2007

The east wing was on the corner of Mortimer Street and Cleveland Street (right). The main entrance was set slightly back in a courtyard between the two wings. The courtyard was once the Hospital's car park (left). The lower floor windows are boarded up prior to demolition.

The upper floors at the north end (back) of the Hospital were connected to the Courtauld Institute by a bridge over Riding House Street. Now the bridge is no more.

N.B. Photograph dated August 2008

Work has begun on the site. The chapel is shown with the Nassau Street facade behind.

N.B. Photographs below dated April 2009

The Hospital has been demolished and the empty site awaits redevelopment (left). Signage for the ill-fated Noho Square development is still present in September 2010 (right).

The east wing was on the corner of Mortimer Street and Cleveland Street (right). The main entrance was set slightly back in a courtyard between the two wings. The courtyard was once the Hospital's car park (left). The lower floor windows are boarded up prior to demolition.

The upper floors at the north end (back) of the Hospital were connected to the Courtauld Institute by a bridge over Riding House Street. Now the bridge is no more.

N.B. Photograph dated August 2008

Work has begun on the site. The chapel is shown with the Nassau Street facade behind.

N.B. Photographs below dated April 2009

The Hospital has been demolished and the empty site awaits redevelopment (left). Signage for the ill-fated Noho Square development is still present in September 2010 (right).

The chapel survives, surrounded by a sea of rubble.

Building of the chapel began in 1891, but was not completed until 1929, when demolition of the old Hospital building allowed access to the east side. The interior Italian Gothic style vaults are decorated with marble and mosaic, and all the jewels mentioned in the Bible. The chapel can hold 80 people.

The Post Office Tower (also known as the BT Tower, British Telecom Tower and London Telecom Tower) is now plainly visible beyond the chapel.

To the west of the west wing of the 'H'-shaped building, on the corner of Mortimer Street and Nassau Street, No. 10 Mortimer Street, an Arts and Crafts Tudor building built of red brick and Portland stone in 1898 (now Grade II listed), had originally been offices for an iron founders, but was soon incorporated into the Hospital.

The facade along Nassau Street has been preserved and is held up by

scaffolding (left). The back of the Nassau Street elevation, as

seen from Riding House Street (right).

The building facade at the north end of Nassau Street bears the legends The Middlesex Hospital and Meyerstein Institute of Radio-therapy (left). The entrance to the Cancer Wing in the central section of Nassau Street (right).

The Out-Patients Department in Cleveland Street, once the Cleveland Street Infirmary, is boarded up, also awaiting redevelopment. It was not included in the sale of the main site, but in August 2010 an application for planning permission was submitted by UCH to Camden Council.

John Astor House in Foley Street, once the Nurses' Home, is still in use as accommodation and administrative offcies for UCH staff (left). The foundation stone laid in 1929 (right).

The west side of John Astor House (left) and the main entrance (right).

The MacDonald-Buchanan School of Nursing in Ogle Street.

The southern side of the Courtauld Institute bears the scar of the doorway to the bridge across Riding House Street (left). The northern elevation of the building on the corner of Cleveland Street and Foley Street (right).

The name of the Samuel Augustine Courtauld Institute of Bio-chemistry is engraved on the side of the building in Cleveland Street.

The Institute was almost not built as an underground river was discovered to be running under the foundation. Samuel Augustine donated more money so that the problem could be overcome.

In a cavity beneath the foundation stone was placed a cutting from The Times announcing the gift, a copy of the Medical School prospectus, a copy of the Middlesex Hospital Journal and a selection of hormone preparations made in the Biochemistry Department.

The main entrance to the Courtauld Institute in Riding House Street.

UPDATE: October 2012

Work has begun again on the site, now called Fitzroy Place.

UPDATE: June 2013

Fitzroy Place (above and below), being built by Derwent London, will contain offices and offices, as well as 235 suites and apartments, in blocks grouped around a public square. The project is expected to be completed by the autumn of 2014.

UPDATE: March 2015

Fitzroy Place at the corner of Mortimer Street and Cleveland Street has almost been completed.

Fitzroy Place at the corner of Cleveland Street and Riding House Street.

The Windeyer Building of the Middlesex Hospital Medical School at the corner of Howland and Cleveland Streets has been demolished. The Sainsbury Wellcome Centre has been built in its place.

UPDATE: January 2016

The Grade II* listed chapel has been restored internally and externally by Caroe & Partners at a cost of £2m. It has been renamed the Fitzrovia Chapel (although to the cognoscenti it will always be the Middlesex Hospital chapel).

The circular 'liturgical east' end (the chapel actually lies on a northwest-southeast axis) contains the altar.

Pearson Square contains the chapel and a modern sculpture - The One and The Many - by Peter Randall-Page.

The previous entrance to the chapel was from a corridor inside the Hospital. Today the central door in the ante-chapel (shown above) is left open when the chapel is not in use and its interior can be seen through a glass screen in the restaurant Percy & Founders. The organ loft is above the doorway.

The decorated archway.

The Baptistery in a side-apse on the eastern side.

The green marble font, copied from the font in the church of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, has symbols of the four Evangelists at each corner. It is incribed with the Greek palindrome NIPSON ANOMEMATA ME MONAN OPSIN (wash away my sin and not only my face).

The windows of the side-apse on the opposite side to the Baptistery.

The stained glass windows (above and below) were all renovated off-site and then re-installed.

The vaulted ceiling (above and below) is covered with mosaic tiles.

The apse in the liturgical east end of the chapel contains the altar.

The altar.

The Nassau Street frontage has been incorporated into the new apartment block.

The facade bears the legend The Middlesex Hospital Radium Wing at third floor level, while the signage above the door reads The Meyerstein Institute of Radio-Therapy - the only remaining signs, apart from the chapel, that the Hospital existed.

The foundation stone of the Barnato-Joel Wing on the Nassau Street frontage.

No. 10 Mortimer Street has also been refurbished.

Readers' comments

"I

am a Registered Nurse who trained at the Middlesex Hospital and the

author of an online petition calling upon the City of Westminster to

commemorate the legacy of the Hospital by renaming the area previously

occupied by it to 'Middlesex Hospital Square'.

The petition may be viewed, and signed at:

www.gopetition.com

Currently there are over 950 signatures to the petitition. Signatories include local residents, former patients, many renowned medical professionals and world-famous actors, including Sir David Jason who states 'I think it is an important mark of respect to all the people who trained and worked at the Middlesex Hospital, for the benefit of many, to name the site in question as the Middlesex Hospital Square. Noho Square is just a ghastly prospect and stands for nothing....'.

David Marriott, Delta, B.C., Canada

The petition may be viewed, and signed at:

www.gopetition.com

Currently there are over 950 signatures to the petitition. Signatories include local residents, former patients, many renowned medical professionals and world-famous actors, including Sir David Jason who states 'I think it is an important mark of respect to all the people who trained and worked at the Middlesex Hospital, for the benefit of many, to name the site in question as the Middlesex Hospital Square. Noho Square is just a ghastly prospect and stands for nothing....'.

David Marriott, Delta, B.C., Canada

(Author unstated) 1898 The Middlesex Hospital. Nursing Record and Hospital World, 4th June, 451.

(Author unstated) 1899 An objectionable innovation. Nursing Record and Hospital World, 23rd September, 242-243.

(Author unstated) 1908 A maternity ward at Middlesex Hospital. British Journal of Nursing Supplement, 17th October, 824.

(Author unstated) 1910 Schools of Midwifery. The Middlesex Hospital. The Midwife (British Journal of Nursing Supplement), 27th August, 179.

(Author unstated) 1912 The Middlesex Hospital. British Journal of Nursing, 6th April, 272.

(Author unstated) 1917 List of the various hospitals treating military cases in the United Kingdom. London, H.M.S.I.

(Author unstated) 1926 The Middlesex Hospital. British Journal of Nursing (March), 63.

(Author unstated) 1929 The Middlesex Hospital. British Journal of Nursing (February), 42.

(Author unstated) 1930 Nursing echoes. British Journal of Nursing (June), 144.

(Author unstated) 1931 A Residential College for Nurses at the Middlesex Hospital. British Journal of Nursing (July), 194-195.

(Author unstated) 1934 "For gallantry". British Journal of Nursing (March), 59.

(Author unstated) 1935 Middlesex Hospital reconstructed. British Medical Journal 1 (3883), 1185.

Backhouse M 2001 The Middlesex Hospital. The Seaxe 37, 9-11.

Barry G, Carruthers LA 2005 A History of Britain's Hospitals. Sussex, Book Guild Publishing

Black N 2006 Walking London's Medical History. London, Royal Society of Medicine Press

Saunders HS 1949 The Middlesex Hospital 1845-1948. London, Max Parrish.

Shaw CD, Winterton WR 1983 The Middlesex Hospital. The Names of the Wards and the Story They Tell. London, The Friends of the Middlesex Hospital.

http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org

http://londonist.com

http://manchesterhistory.net

http://news.fitzrovia.org.uk

http://timandrewsoverthehill.blogspot.co.uk

https://en.wikipedia.org

www.derelictlondon.com

www.fitzroviajournal.com

www.flickr.com (1)

www.flickr.com (2)

www.thelancet.com

www.ucl.ac.uk

www3.westminster.gov.uk

Return to home page