Military

In August 1914 the Royal Victoria Patriotic School in Wandsworth became the Third London General Hospital. Of the four Territorial General Hospitals in London, it was the one that had needed the most structural alterations.

The building had been originally been erected in 1859 as the Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum, an orphanage for the daughters of former soldiers, sailors and Marines who had fought during the Crimean War (1854-1856). It had been established and endowed by the Patriotic Fund and the foundation stone had been laid by Queen Victoria. By the turn of the century it had been renamed the Royal Victoria Patriotic School.

On 5th August 1914, the day after war had been announced, the building was requisitioned and the children transferred to local houses nearby for the duration. Twenty NCOs and other ranks arrived under the command of a Major Miller to make the initial preparations, while the Hospital's Commanding Officer, Lt-Col Bruce Porter, negotiated purchase of the necessary equipment. The School's furniture was removed and many structural changes made. WCs and bathrooms were attached to those rooms which would be wards. The windows had to be altered to provide adequate light and air. The entrance hall contained the telephone exchange. The school dining hall, adjoining the entrance, became a reception ward, from which patients were eventually transferred to their appropriate wards. The room was fitted with an emergency theatre in one corner, shut off with heavy screens. A bronze statue of Lord Kitchener had been placed in a conspicuous position. Electric lifts and kitchen accommodation were installed. By 15th August the Matron and 50 nursing staff were on duty, the beds and theatre were ready and the Hospital was ready to receive patients.

The main building contained wards for medical and surgical cases, with two large wards for ophthalmic patients. There was also a padded room for insane patients. The X-ray Department enabled bullets to be located within wounds and, in many cases, to be found where their presence had not been expected. The School infirmary, a separate building a small distance away from the main building, became a Nursing Home for officers. This building also contained a temporary, fully stocked operating theatre while the hutted theatre was being built.

However, it soon became apparent that the building was too small. It could only accommodate 200 beds - and each Territorial General Hospital was required to have 520 beds.

The first of the extensions was built within eight weeks in the large grounds of the estate, and consisted of a series of 10 hutted wards, each containing 20-25 beds, placed either side of a long covered way which was connected to the School building. The huts were built of corrugated iron covered with asbestos felt, painted to make it impervious to the weather. Each hut had a verandah. The bathrooms and WCs were connected to the main drain passing through the estate. One of the huts was set aside for use as an operating theatre. A water tank was built at a considerable height above the temporary hutted buildings to provide water in case of fire. The kitchens were supplied with hot water mess tins for the conveyance of food to feed the growing number of patients.

At some distance from the main building was an isolation camp for infectious diseases cases. The staff were housed in tents in an outlying field, while huts were built for them there in readiness for winter. Nursing staff were accommodated in three villas a short distance from the Hospital (a fourth one was later acquired).

Some existing out-buildings were adapted to become the operating theatre and sterilizing room. One of the buildings became the Pathology Laboratory. It had hot and cold storage for bacteria, a destructor and a disinfector, and a mortuary and post-mortem room.A temporary railway station was built in front of the building to enable the wounded to be brought easily to the Hospital from the south coast.

The medical staff were seconded from the Middlesex Hospital, St Mary's Hospital and University College Hospital. While the building works were going on, the Hospital received some 120 wounded men from the front or from the Territorial Force (who were mainly suffering from 'young soldiers' complaints). A section of the Territorial General Hospital was established at the Middlesex Hospital.

In May 1915 all Territorial General Hospitals were required to establish Neurological Sections, for the treatment of patients with shell shock or neurasthenia.

In August 1915 Lt. Col. Bruce-Porter requested the British Red Cross Society to provide workers for the administrative departments so that men could be released for the Front. The London/28 Voluntary Aid Detachment (V.A.D.) was chosen for this task and replaced 12 men in the record office, linen store, post office, Steward's store and other departments. Despite having to contend with the natural prejudice of the N.C.O.s and orderlies, the women coped well and the experiment was deemed successful. Other hospitals soon followed suit, replacing servicemen with V.A.D.s.

In February 1916 the new High Commissioner for Australia, Mr Andrew Fisher, visited the Hospital with his wife, and spoke to every Australian patient in the building.

More hutted wards were added beyond the original Hospital grounds, being built on land which had been prepared by the LCC as a recreational place for Wandsworth residents. By February 1917 the Hospital had 1800 beds. The ward huts were called 'Bungalow Town' and included a new operating theatre, an X-ray Department, kitchens, a recreation room, bathrooms, storerooms and a boardroom. The new patient accommodation enabled part of the School building to be used for administrative offices. By May the Hospital had almost 2,000 beds, including 208 for eye cases, 28 for TB patients and 18 for those with dysentery; 168 patients were housed in detachment huts. By November 1917 some 897 officers and 987 enlisted men were being treated. At this time, of the 40,000 patients who had been admitted since the beginning of the war, only 270 had died.

The Hospital had three mortuary chapels, equipped with altars, candles and crucifixes. One chapel contained an ivory crucifix which had been donated by Queen Amelie of Portugal.

Several of the patients had suffered severe injuries to the face and Francis Derwent Wood (1871-1926), a sculptor who was too old to enlist but did voluntary work at the Hospital, suggested to the War Office that he could restore the contour of the face by artificial means. His offer was gratefully accepted and he established the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department (known colloquially as the 'Tin Noses Shop'). After taking a cast of the disfigured face, he constructed a prosthetic mask of silvered copper, sculpted to resemble a portrait of the patient before injury. Painted to match the patient's colouring, the prosthesis was held in place by a pair of spectacles. Even though the masks proved uncomfortable, they renewed the patients' self-confidence and enabled them to return home to their jobs and families. (More than 20,000 men were injured in the face during the war.)

Many men had been recruited as RAMC orderlies from the Chelsea Arts Club. Considered too old, unfit or otherwise unsuitable for military service, this group consisted of artists, writers and sculptors. Between them, they produced one of the finest hospital magazines - The Gazette of the 3rd London General Hospital - which was published monthly throughout the war from an early date.

The Hospital closed in August 1920. During the six years of its existence it had treated 62,708 patients from all over the British Empire.

Present status (December 2009)

The building is now the Royal Victoria Patriotic Building. It contains 29 apartments, several studios and workshops for designers, artists and craftsmen, as well as a drama school - the Academy of Live and Recorded Arts - and a French restaurant - Le Gothique.

The front elevation of the Royal Victoria Patriotic Building.

The central tower (left) bears a statue of St George and the Dragon (right).

The chapel is located to the left and rear of the main building.

The original gateposts remain.

Site maps showing the layout of the building and present location of the workshops and apartments.

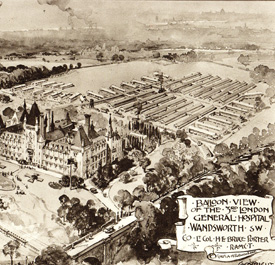

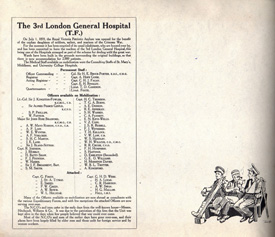

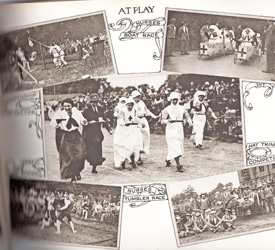

These photographs are reproduced from A Souvenir of London and the 3rd London General Hospital, published in 1919 by Photochrom, and presented to discharged patients and to members of the staff for services to the hospital.

A panoramic view of the Hospital, showing the ward huts behind the school building.

The frontispiece of the book, listing the medical staff. The opening paragraph states:

The 3rd London General Hospital (T.F.)

On June 1, 1859, the Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum was opened for the benefit of the orphan daughters of soldiers, sailors , and marines of the Crimean War.

For the moment it has been emptied of its usual inhabitants, who are housed near by, and hav been coverted to form the nucleus of the 3rd London General Hospital, this being one of the Hospitals arranged as part of the scheme for dealing with the great war.

Wards have been built in the grounds surrounding the original buildings, so that there is now accommodation for 2,000 patients.

The Medical Staff available on mobilization were the Consulting Staffs of St. Mary's, Middlesex and University College Hospitals.

Many recreational activities were arranged for the staff.

(Images courtesy of Christine Gillet, whose great aunt was presented with the book).

After WW1 the building became an orphanage once more until 1938, when the children were evacuated to Hertfordshire because of the threat of another war. They never returned to London and the orphanage finally closed in 1972.

During WW2 the building was used by MI6 as a clearing, detention and interrogation centre. After the war it became a teacher training college and then, in the 1950s, a school. By the 1970s it had become run-down and in need of repair. The school closed and the building was then badly vandalised. It was suggested it should be demolished, but pressure from conservation groups led to it being Grade II-listed (now Grade II*). In 1980 the Greater London Council put the building up for sale, but the £4m needed for its restoration proved a deterrent to would-be buyers. It was eventually sold for £1 to a property company on condition they restore it. The restoration and conversion work took six years - three times as long as it took to build the Asylum originally.

(Author unstated) 1914 The reception of the wounded. The London Territorial Hospitals. British Medical Journal 2 (2803), 518.

(Author unstated) 1914 The Hospital World. 3rd London General Hospital TFNS. British Journal of Nursing, 26th September, 251.

(Author unstated) 1914 The hospitals and the war. 3rd London Territorial Hospital. British Medical Journal 2 (2806), 644-645.

(Author unstated) 1915 The Third London General Hospital. Hospital 59, 79-80.

(Author unstated) 1916 Nursing and the war. British Journal of Nursing, 12th February, 137.

(Author unstated) 1917 List of the various hospitals treating military cases in the United Kingdom. London, H.M.S.O.

(Author unstated) 1917 Third London General Hospital, Wandsworth. British Journal of Nursing, 24th November, 339-340.

(Author unstated) 1920 The Nursing World. British Journal of Nursing, 28th August, 118.

(Author unstated) 1925 The British Red Cross Society. County of London Branch Annual Reports 1914-1924. London, Harrison & Sons.

Muir W 1917 Observations of an Orderly. London, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.

Sleigh S 2014 Mutilated WW1 soldiers given hope by a Wandsworth Hospital. Sutton & Croydon Guardian, 4th August.

http://thirdlondongeneral.blogspot.com

https://blackcablondon.net

https://boroughphotos.org

https://wellcomecollection.org

https://ww1wandsworth.wordpress.com

www.archive.org

www.awm.gov.au

www.flickr.com

www.fulltable.com

www.gilliesarchives.org.uk

www.gwpda.org

www.rootschat.com

www.rvpb.com

www.vlib.us

Return to home page