Royal Free Hospital

256 Grays Inn Road, Holborn, WC1X 8LD

Medical dates:

Medical character:

1828 - 1974

Acute. Teaching hospital.

Following a meeting on 14th February 1828 in the Gray's Inn Coffee House held by Dr. William Marsden (1796-1867) and 27 of his friends from the City of London, it was decided to establish a hospital which would provide free treatment for poor people without the need of a subscriber's letter, as demanded by other voluntary hospitals. Marsden had been motivated by finding a young girl dying on the steps of St Andrew's Church, Holborn. She had been refused admission to three hospitals because she had no subscriber's letter, so he cared for her himself until she died two days later.

The

London General Institution for the Gratuitous Cure of Malignant

Diseases opened on 17th April 1828 in a rented 4-storey house at 16

Greville Street, Hatton Garden. Initially it was only a

dispensary, but soon had 30 beds.

Treatment was free to all comers.

In 1832 it was the only London hospital to treat cholera victims.

During the epidemic all space in the Institution was made

available.

In September 1833 its name was changed to the London Free Hospital. Two years later, following a petition to King William IV for his approval, it became simply the Free Hospital. However, when Queen Victoria became its patroness in 1837, in recognition of its work during the cholera epidemic it became the Royal Free Hospital.

In 1839 the house next door, at No. 17 Greville Street, was

acquired and the Hospital then had 72 beds.

On 31st August 1842 the Hospital took a lease on larger premises - the former barracks of the Light Horse Volunteers in Grays Inn Road - while a public appeal was launched for funds.

In 1844 the Hospital moved to Grays Inn Road. The barracks consisted of a quadrangle with a north and a south wing, and a block at the rear of the courtyard.

The north wing was made into two wards, a Board Room and administrative offices, while the south wing contained one ward and consulting rooms. At the back of the quadrangle were two more wards and the kitchen. The Hospital had 152 beds and the patients lived much in much the same conditions as the soldiers had done before them.

Gradually the buildings were improved or replaced. The north wing - the Sussex Wing, named after the late Duke of Sussex, a notable benefactor of the Hospital - was rebuilt by the Freemasons in 1856.

Work began to replace the south wing in 1876. Completed in 1879, it had 50 beds and a large Out-Patients Department. It was named the Victoria Wing, after the Queen.

It became a teaching hospital in 1877, allowing

female

medical students access to clinical practice on its wards - the only

hospital, apart from a short period during WW1, to accept female

medical students before 1947.

The western elevation fronting Grays

Inn Road with the main entrance was rebuilt in 1893. It was

officially opened on 22nd July 1895 by the Prince and Princess of Wales

(later to

become King Edward

VII and Queen

Alexandra) and was named the Alexandra Building.

A laundry was also built on vacant land at the rear of the Hospital site.

In 1895 the Hospital was the first to appoint an Almoner - the precursor to a social worker - whose job it was to care for the non-clinical needs of patients.

In 1907 two new operating theatres and their annexes were built on top of the Sussex Wing. In 1909 the Hospital had 165 beds.

In 1912 an anonymous donor donated £14,000 so that a piece of land at the rear of the Hospital could be purchased on which which to build a new Out-Patients Department and maternity unit. The donor was later discovered to be Alfred Langton, the new Chairman of the Board of Governors, who had previously been Chairman of the Board at Hampstead General Hospital.

The new block was completed in 1915 and was named the Helena Building. It contained a large Out-Patients and Casualty Department, an Electrical Treatment and Massage Department, an X-ray Department, a dispensary, an Almoner's office, an Obstetrics and Gynaecological Department with three wards, and student quarters.

Before it could open, the building was requisitioned by the War Office and became the Royal Free Military Hospital for officers. This military section contained 150 beds, each with its down quilt, covered for the most part with plain green silk (some with blue silk). Green screens and green chairs harmonised with bed quilts, giving an impression of restfulness and ease. There was a common room for those patients who were ambulant. The section, of course, had an up-to-date X-ray room with adjoining Massage Department.

Following demobilisation of the military section in 1918, the War Office returned the Helena Building to the Hospital. In 1920 the upper part became the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department. Queen Mary visited the Hospital on 11th May 1921 to open the new unit, which had 68 beds. It was named the Queen Mary Maternity Department after her.

One part of the Obstetric section was named Washington and another Marlborough, in recognition of the financial assistance given by the American Red Cross (which had given £10,000), the American Women's Club and the Duchess of Marlborough. (Since 1918 some 33 maternity beds had been in the Endsleigh Street Annexe, which consisted of five houses leased from the Duchess of Marlborough.)

The Obstetric Ward was homelike, with the babies' cots by the side of each bed rather than at the foot of it. Mothers wore a blue dressing gown or bed jacket faced with cream and blue. Labour gowns opened at the back, while nightgowns were specially made so that feeding could be carried on without uncovering the mother. The baby had a little dress or gown, flannel and vest, all of which fitted one inside the other, so that there was no unnecessary turning of the child. The babies' bathroom contained a porcelain stand of four baths and there were shelves, divided into numbered compartments (two for each baby - one contained everything necessary for washing purposes and the other a special bowl for the lotion used to swab the baby's eyes). Underneath these were hung towels bearing the same number.

The gynaecological wards had an operating theatre and an anaesthetic room attached.

A special Appeal was made to raise £50,000 to build a children's ward. By 1925 some £21,250 had been raised by subscriptions, including £5,000 from Alfred Langton, Chairman of the Board of Governors since 1912. Lord Riddell, the President of the Hospital, made up the amount to £25,000. (The Hospital was able to modernise mainly due to the financial generosity of Lord Riddell, Alfred Langton and Sir Albert Levy, the Honorary Treasurer.)

The Alfred Langton Home for Nurses opened in Cubitt Street in 1925. It could accommodate 65 nurses and 25 maids.

Work began on the new children's wards, which were built on the roof of the Victoria Wing. They were named the Riddell Wards for Children and were officially opened by Queen Mary on 28th February 1927. The wards contained 20 cots for boys up to the age of 10 years and girls up to 12 years. Open balconies had been provided for fresh air treatment.

In 1927 the Hospital had 268 beds.

To celebrate its centenary in 1928 the Hospital planned further extensions and a fresh Appeal was launched. When fund-raising faltered, Albert Levy donated £55,000 towards the cost of the new building. For this generosity, the new maternity section was named the Albert Levy Wing.

In 1929 the Eastman Dental Clinic opened in a building adjacent to the Hospital, providing free dental care for children.

The new building, named the Queen Mary Building, opened on 8th June 1932. It had cost £250,000 and contained, among others, V.D., Orthopaedic and Physical Medicine Departments. New kitchens had also been installed.

In 1932 the Queen visited the Hospital to open the Albert Levy Wing and to lay the foundation stone of an extension of the Alfred Langton Nurses' Home, which was to cost £60,000. The Nurses' Home was eventually completed at a cost of £150,000, and could accommodate 250 nurses. It was renamed the Langton-Riddell Nurses Home.

By 1934 the mortality rate in the maternity wards was 2.8 per 1,000, the lowest in London. An operating theatre and two new wards with 30 beds had opened for ear, nose and throat patients. The number of beds for private patients had been increased to 28. The Albert Levy Wing had been brought into full operation, comprising an Out-Patients Department for obstetric and gynaecological cases, an Electrotherapeutic and Massage Department, a central kitchen with modern equipment and a boiler house. The Hospital had 315 beds and was treating on average 1,000 patients a day, including 100 children in the Eastman Dental Clinic.

In 1939, at the outbreak of WW2, the Hospital had 327 beds and one of the largest Out-Patient Departments in London.

The Ministry of Health contributed to the cost of bomb-proofed underground operating theatres and shelters and to a 50 ft (15 metres) deep bore-hole to store radium during air-raids. The Hospital joined the Emergency Medical Scheme, with its staff jointly running Sector III hospitals with St Bartholomew's Hospital. However, in October 1939, the teaching staff and 1st Year medical students were evacuated to St Andrews, while 2nd and 3rd Year students were sent to Aberdeen University. Following a lull in the air-raids, they returned to London at the end of 1940.

On 5th July 1944 the Victoria Wing was severely damaged by a V1 flying bomb. Although there were not many casualties, 120 beds were lost and only 4 were immediately usable afterwards. Some 140 patients were evacuated. The Hospital rented 100 beds from the London Fever Hospital for children and obstetric and gynaecological patients, and 300 beds at the Three Countries Emergency Hospital at Arlesey (until 31st December 1947).

On 9th February 1945 a V2 rocket destroyed the end of the Laboratory Wing in Hunter Street.

In 1946 the Hospital had 318 beds.

The Hospital joined the NHS in 1948 as a Teaching Hospital under the control of the Royal Free Group Hospital Management Committee. Other Hospitals in the Group were the Children's Hospital, Hampstead, the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital, the Hampstead General Hospital and the London Fever Hospital.

The war damage was gradually repaired. The Victoria Wing

was rebuilt as the New Wing, while the eastern block at the rear of the

quadrangle was renamed the Victoria Building.

In August 1955 the Hospital was forced to close for the first time in

its history due to an outbreak of mononucleosis (glandular fever) among

its nursing staff. The 240 patients were transferred to other hospitals.

After the war it had been felt that the Grays Inn Road site was too

cramped and that there were too many teaching hospitals in central

London. Plans to replace the Royal Free Hospital with a new

building on the site of the Hampstead Fever Hospital

in Lawn Road were drawn up, but work did not begin on the site until

1968.

In 1968 Coppetts Wood Hospital and New End Hospital joined the Group and, in 1972, Queen Mary's Maternity Home.

The Hospital closed in 1974 when the new Royal Free Hospital opened in Pond Street, the first to have been designed with the aid of a computer. It was officially opened by the Queen in 1978 (on its 150th anniversary).

|

Present status (January 2008) The Nurses' Home is now a student hostel for University College London. |

|---|

The front elevation of the former Royal Free Hospital along Grays Inn Road. The Sussex Wing is at the far left, beyond the Alexandra Wing.

The main entrance is through a central archway, leading to a courtyard. The legend 'Royal Free Hospital' is still visible under the pediment. 'Eastman Dental Hospital' is inscribed on the stonework to the left of the archway.

The fountain in the inner courtyard with a cherub on top clutching a dolphin was installed in 1931. The inscription around the rim reads This fountain has been erected and the courtyard beautified by the Honorary Treasurer Sir Albert Levy who has also endowed a fund for their maintenance as a permanent memorial of thanksgiving for the restoration of health of the President of the hospital the Rt Hon Lord Riddell.

The fountain had been removed in 1938 and remained in storage until August 1994, when it was restored to its original site by the Eastman Dental Hospital.

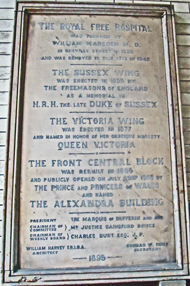

The plaque listing the dates of the development of the Hospital is

displayed on the wall of the archway entrance.

The northern elevation of the Sussex Wing, showing the depth of the building. The 1907 extensions can be seen on the top floor.

The southern elevation of the Queen Mary Building, as seen from St Andrew's Gardens.

The Nurses' Home in Cubitt Street (later Langton Close) is now a student hostel - the UCL Hostel, Langton Close.

The rear elevation of the former Nurses' Home, as seen from St Andrew's Gardens.

Frances Gardner House, another UCL hostel, opened in 2004. The 8-storey building was erected at a cost of £8m. It replaced former Hospital buildings on the site, but part of an old wall still remains (right).

The London School of Medicine for Women was founded in 1874. Its medical students were allowed access to the wards at the Royal Free Hospital for clinical training in 1877. At the end of the 19th century the School moved to this purpose-built building in Hunter Street.

In 1898 the School changed its name to the London (Royal Free Hospital) School of Medicine for Women. The signage has been preserved above the door.

The Grade II listed building is now the Hunter Street Health Centre. A plaque to the left of the entrance is inscribed Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine (University of London).

References (Accessed 24th October 2014)

Amidon LA 1996 An Illustrated History of the Royal Free Hospital. London, Special Trustees for the Royal Free Hospital.

(Author unstated) 1915 The Royal Free Hospital. Dedication of the military section. British Journal of Nursing, 4th December, 456-457.

(Author unstated) 1921 The Queen's visit to the Royal Free Hospital. British Journal of Nursing, 21st May, 305-306.

(Author unstated) 1925 The Royal Free Hospital. British Medical Journal 1 (3363), 1097.

(Author unstated) 1932 Nursing echoes. British Journal of Nursing (July), 173.

(Author unstated) 1934 Progress at the Royal Free Hospital. The Midwife (May), 140.

(Author unstated) 1966 New Royal Free Hospital. British Medical Journal 1 (5482), 289.

Black N 2006 Walking London's Medical History. London, Royal Society of Medicine Press.

Medical Staff of the Royal Free Hospital 1957 An outbreak of encephalomyelitis in the Royal Free Hospital Group, London, in 1955. British Medical Journal 1 (5050), 895-904.

http://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com

www.collectionspicturegallery.co.uk

www.flickr.com (1)

www.flickr.com (2)

www.flickr.com (3)